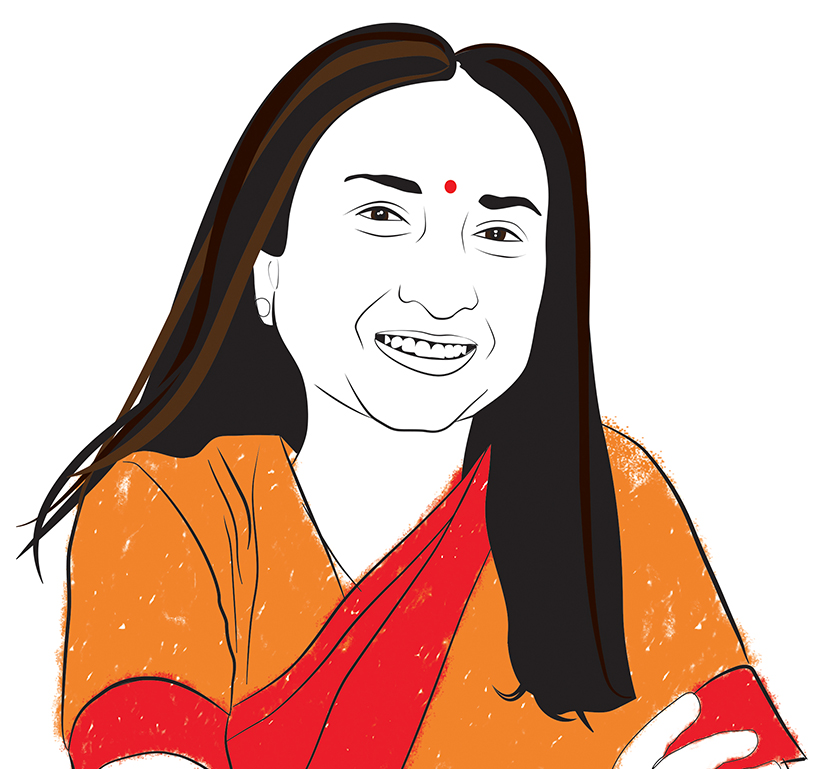

As Manchester celebrates 60 years of development studies, Professor Bina Agarwal, based at the University’s Global Development Institute, looks at the problem of everyday harassment of women, from Hollywood to the Global South.

I usually take the 142 bus from East Didsbury to the University, where I teach. I always find a seat. I read or prepare class notes, and some 40 minutes later hop off near my office. Comfortable. Safe.

But for women travelling to work in the cities and small towns of South Asia, in buses, trams and trains, clutching bags with one hand and roof straps with the other, the journey to work can be nightmarish. Men may fall on you ‘innocently’, touch you inappropriately, lean too close or simply stare at you, unblinking.

Or consider the whistling, winking, beckoning and lewd singing that may follow you down the street. This was not uncommon in many western countries until quite recently, and it persists in many cities of the Global South. The male gaze, so romanticized in Hollywood and Bollywood films well into the 1980s, remains on the streets.

The #MeToo movement has revealed the dark underbelly of men’s behaviour in the entertainment industry, the corporate world, and at workspaces and universities globally. But if you ask women about the everyday forms of harassment they face at work, in pubs and on the Internet, their voices would reach a crescendo. Almost everyone would shout: Yes, Me Too!

Most forms of workplace harassment are difficult to define or prove – when the call-centre supervisor leans too close across your shoulder, several times a day, or when your boss pats you in a ‘fatherly’ way. The laws on sexual harassment can’t touch these insidious manoeuvres that leave women angry and mortified. They’re even less able to deal with the experience of most women globally who don’t work in offices or cities.

Their workspaces are everywhere: farms, construction sites, even pavements where they sell their wares. And the watchdogs, the local police, may themselves be predators.

In this pervasive culture of harassment, there have been rare exceptions. The ancient Garos were a classless matrilineal society in north-eastern India. Both sexes enjoyed sexual freedom but there was zero tolerance for men’s unwanted advances towards women. Whistling, suggestive comments, grasping a woman’s wrist or assaulting her while supine – all were punishable. It was a moral code of conduct, not a moralistic code. It was enforced if women reported transgressions to the village chief. And that was 100 years ago!

Today, although many countries have laws against sexual harassment, these are not enough. Speaking out is essential, but often women hesitate. What women want is not reporting of misbehaviour but an ingraining of good behaviour.

Today, typically men exercise power over women across spheres: economic, legal and social. But what if more bosses were female? If women controlled the media, reclaimed the streets, set the social norms? For this, the #MeToo movement must link with efforts towards equality for women across all spheres. And men must join the movement. Only then can we transform, and not merely tinker with, gendered codes of conduct.

We have barely started. Come on, what are you waiting for?

Bina Agarwal is Professor of Development Studies and Winner of the 2017 Balzan Prize for Gender Studies.

Find out more about our research into global inequalities

Read more about the 60 years of development studies at Manchester