In Manchester, art galleries and museums share the same radical, rebellious and inclusive nature as the city itself. No hushed corridors here; these are places open for exploration; brimming with life; reflecting our experiences back to us. The message from Alistair Hudson and Esme Ward, two of the University’s newest cultural figureheads, is clear: everyone’s invited.

Both the University’s Whitworth and Manchester Museum have new directors at their helms. Alistair Hudson became Director of both the Whitworth and the city council-run Manchester Art Gallery in February. He succeeded Maria Balshaw, now leading Tate, who oversaw the Oxford Road gallery’s lauded £15 million transformation project.

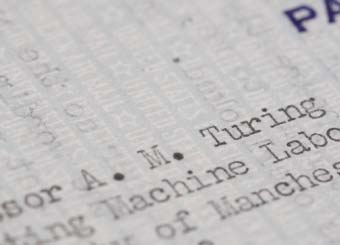

A champion of the ‘useful art’ movement – the idea that art should be a tool for social change and education, not merely an object of contemplation – Alistair was previously director of the Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (mima) and sat on the 2015 jury for the prestigious Turner Prize.

Down the road at Manchester Museum, Esme Ward became its first female Director when she took up her post in April. She was previously Head of Learning and Engagement at both the Museum and the Whitworth.

For both, their ambition is bold, community-focused and future-facing.

Alistair Hudson at the Whitworth

Putting art to use

Breaking from work on the gallery’s textiles exhibition, Four Corners of a Cloth, to chat in the serenity of its glass-boxed retreat, Cafe in the Trees, Alistair throws a grey blazer over the casual get-up and trainers of a hands-on curator. “The big ambition, for me, is to change the way people think about art – to normalise it in life and stop making it exceptional,” Alistair, who’s also Honorary Professor of Useful Art at the University, explains.

“I imagine this place a bit like a house for everybody. You’ve even got a garden. A lot of my philosophy is around what I call ‘usership’: people using these spaces at the heart of a programme of social change. People don’t meet as they used to, at school or church, so I see museums and galleries as empathy machines.

“Galleries and museums are typically constricted to generating a particular type of behaviour: look at something and feel better. I’m expanding that, putting the art to use.”

Alistair’s mind comes alive with ideas: installing an MRI scanner in the gallery to study the brain’s responses to the art, or art for robots by robots. Call it ‘live art’ or, as he does, citizen science.

Useful art, he says, is not a new idea but a ‘ground-up’ version of the Victorians’ patriarchal institute movement; the Whitworth itself was built in 1889. “They built art galleries, collections, museums for social purpose. At times it was a little bit instrumental – to get workers out of the pubs and into education and make them behave properly so they would fire Britain forward. But through that process people collectivised and congregated.”

Manchester’s a proper salty place. It’s a place to do the democratic, open, more down-to-earth version of an art gallery.

He’s eager to diversify the range of people visiting the gallery, pointing out that these places were created for the people of Manchester, not as tourist attractors.

“It’s part of our remit – both the University’s and the government’s social agendas – to take art to the community. But I believe in it anyway.”

The Whitworth, the Museum and the University’s Jodrell Bank Discovery Centre and the John Rylands Research Institute and Library have comprehensive social responsibility programmes in place. Cultural Explorers, for example, provides free cultural entitlement for all local Year 5 primary school pupils to visit one of them.

Alistair adds: “There are some instances, I won’t say which, where a museum quite likes being a rarefied institution for the elite. But Manchester’s a proper salty place. It’s a place to do the democratic, open, more down-to-earth version.”

Alistair Hudson and Esme Ward

First sparks

Alistair and Esme’s cultural journeys had different beginnings. For Alistair, it started early.

Raised locally, he had art on the brain as a child. “I was unsure whether I wanted to be an artist or a curator-type. At school I hung around the art room more than anywhere else. As a teenager I worked in an engineering warehouse in the holidays and went into the city’s art gallery for my lunchtime reprieve from the oil and dirt.

“I spent my evenings at the Hacienda which, in a way, was a kind of art school. Before it got really famous it was like a weird Warhol-esque arts club where about 23 people hung out on a Wednesday night. It was art as a way of living – that whole philosophy of giving the working classes a right to be pretentious too. That creativity made you think: ‘Yeah, this is a way out.’”

For Esme, the epiphany was slower to arrive, but when it did, it was transformational. “I come from quite a sporty family,” she explains. “I don’t ever remember going to a gallery or museum until I was 19. I was studying in London and I went into what was then known as the Tate Gallery and was absolutely terrified. It just felt bigger than me.

“When I eventually went in, I encountered this whole other world. I remember feeling really angry that I’d not been in it before. I went every weekend for about a year and just lapped it up. If I’d not gone up the steps, I’d have a poorer life.”

Manchester’s a proper salty place. It’s a place to do the democratic, open, more down-to-earth version of an art gallery.

Unlocking imagination

This ‘threshold anxiety’ drives Esme’s ambition to make the Museum – which last year welcomed more than half a million visitors – as relevant as possible to as many as possible.

“Generations of people have been here and take their own children; my job is to make it more deeply and widely loved by yet more people. Relevance will be a big part of that. Unlocking the potential of all these collections will be a really big part of our work moving forward.

“Manchester Museum has four million objects. We have to ask ourselves: ‘What is all the stuff for anyway?’ When the Museum opened there was this wonderful appeal to the civic spirit and scientific curiosity and devotion of the townsfolk of Manchester. That’s what it’s for, in the core of the organisation.”

In the autumn the Museum will partly close for two years as building work starts on a £12 million transformational project. This will bring new exhibition spaces, including the north’s first South Asia Gallery, created in partnership with the British Museum.

A programme called Liberation will launch, asking the public to imagine what would happen if the collections – which range from Ancient Egyptian mummies to hundreds of preserved animals – were set free to find new homes across the city.

Esme, with her favourite heart-shaped red-resin brooch pinned to her dress, explains: “That could be everything from a polar bear going to Chill Factore because it wants snow under its feet again or the spider crab crawling over the road to the edge of the Aquatics Centre.

“It requires a leap of imagination, which is what museums do. We tell a partial story of the collections we hold. What we want to do is find more stories.

“People think that because you work in a museum you are obsessed with the past. Actually, I think I’m obsessed with the future. If you care for the past, you are staking a claim on what matters in the future.

“Museums are in and of their time. We’ve always been a powerful source for learning and we will be evermore so. We’ve worked really hard to be a social space and I’m interested in how we become what I call a ‘pro-social’ space; that is, how do we become not only a site for learning but a site for civic and social action?”

Esme Ward at Manchester Museum

Esme, who’ll co-curate the arts, health and social change programme at the World Healthcare Congress Europe in Manchester in 2019–20, is passionate about the role the University and its cultural institutions take in caring for society. “I see museums as places of care, for collections of course, but also for people, ideas and relationships,” she says. “Care will be at the heart of all we do as we move forwards.

“Some of our collections are insights into some of the things we grapple with most in the world: ageing, climate change, inequalities, diversity. Our collections can contribute to our collective understanding of those issues. It’s about us really understanding and realising our social value.”

We tell a partial story of the collections we hold. What we want to do is find more stories.

Both Esme and Alistair agree that being part of a large university allows these ambitions to become realities. “A university generating new knowledge is such an imaginative context to work within, but also to have that interdisciplinary approach, that breadth of thinking and working, on the doorstep feels incredibly exciting,” beams Esme.

Alistair is similarly fired up by the opportunities for collaboration. “There are a lot of people and brains. These are the spaces where they can collaborate, in public, at the coal face: with people not in the classroom. It makes learning creative.

“If we implement everything I’m talking about, then it’s quite a wholesale cultural change for the art world. I get a lot of resistance from the contemporary art world; there is peer-group pressure to behave as art institutions should behave.

“Sometimes you have to break some rules to do the right thing. We’re at this moment where that has to happen if we’re genuinely going to get art and creativity back into the public consciousness, into education, and start addressing some of society’s problems. Just relying on pictures on walls and selling cups of tea is not going to do it.”

Read more about the creativity at Manchester and our cultural institutions.